Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Tamara Achampong, BSc (Psychology), SIG Co-ordinator and MPhil Psychology & Education Student (Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge)

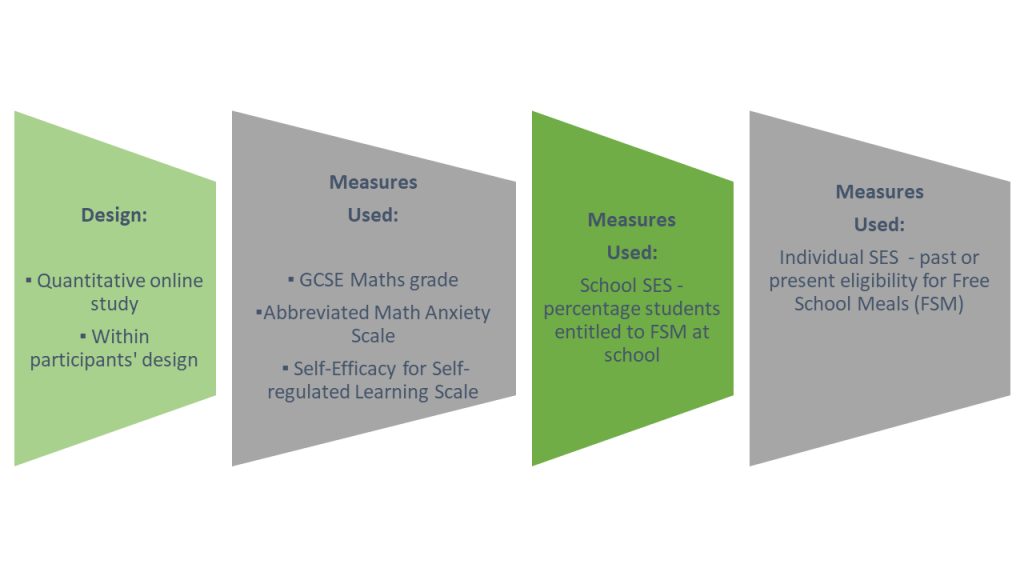

Whilst the relationship between Maths Anxiety and Maths Achievement has been established, the impact of Socio-economic Status (SES) and Self-efficacy for Self-regulation on this relationship has yet to be explored, and this research hoped to shed light on this area.

I was given the opportunity to present this research at the Wolfson College Research Event on 28th April 2021 which you can watch here (Timestamp: 53min to 1h 8min).

Photo by Jessica Lewis on Unsplash

Background Literature

Maths Anxiety & Maths Achievement Relationship

Maths Anxiety is defined as feelings of nervousness and discomfort when solving maths problems or handling numbers [1]. Crucially, Maths Anxiety can have a negative impact on Maths Achievement and learning experience. Individuals with Maths Anxiety are less confident in their maths ability, have negative attitudes towards maths related tasks and are more likely to avoid maths generally and when pursuing careers[2-3]. Research has robustly have confirmed that students with higher Maths Anxiety are more likely to show poorer Maths Achievement [4].

Socio-economic Status (SES)

Socio-economic Status (SES) refers to the economic and social position of an individual in relation to others. SES has been shown to influence Maths Achievement across many different countries, with huge datasets such as PISA [5] illustrating a persistent attainment gap between students from high SES backgrounds and those who are disadvantaged. Similarly, in the UK individual-level SES indicators such as family income and Free School Meal (FSM) status are strong predictors of the GCSE Maths attainment gap [6]. School SES has also been measured within the literature [7] and in terms of student distribution, poorer pupils are more likely to attend a lower SES school, whilst top performing schools tend to be selective and admit relatively fewer pupils who would be eligible for FSM.

The current study used both individual and school SES measures allowing us to draw comparisons between impact of these on the Maths Anxiety and Maths Achievement relationship.

Self-efficacy for Self-regulation

This construct reflects one’s belief about their ability to think and behave in ways that are associated with their learning goals [8]. Research reports that more academically able students have higher self-efficacy for regulation and lower Maths Anxiety than those who were not [9]. Therefore, we hoped to replicate findings within this study using this measure.

Aims

How Did We Study This?

What Did We Find?

- On average students scored low for Maths Anxiety, moderately in Self-efficacy for self-regulation and highly in Maths Achievement.

- We replicated the relationship between Maths Anxiety and Maths Achievement, finding that pupils with higher Maths Anxiety were more likely to have lower Maths grades.

- Found SES differences in Maths Achievement, with participants from lower SES schools and backgrounds being less likely to attain higher maths grades.

- For Maths Anxiety found SES differences at the school level but not the individual level, highlighting that school SES was a better predictor of Maths Anxiety. The literature suggests this may arise due to attributes of the learning environment such as teacher anxiety, teacher attributes, or school resources.[10]

- Self-efficacy for Self-regulation was not found to be associated with Maths Anxiety or Maths Achievement, which differs from literature. This could be explained by characteristics of the students, as on average students had low levels of Maths Anxiety and high GCSE maths grades. This may not be surprising considering the sample consisted of a high proportion of students from high SES schools and backgrounds.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Conclusions

- Results illustrate the SES achievement gap and that there are SES differences in Maths Anxiety.

- Add to the broader discourse on the educational disadvantage gap which COVID 19 has demonstrated is worsening.

- Relates to intervention that currently exists to target Maths Anxiety and subsequent Maths Achievement, such as Johnson-Wilder and Lee [11], who developed the construct of ‘Maths Resilience’ in which they develop this trait through coaching for learners, teachers, and parents.

- Research also links to the necessity for more funding to be available to enable schools to better address this.

Final Thoughs

Why does this matter?

Adds to broader literature on educational inequality which has consistently demonstrated such SES variation in outcomes for learners. The analysis of large cross-country datasets by epidemiologists such as Wilkinson and Pickett [12] in their book the Spirit level has revealed that all children do better in education in more equal societies.

What does this mean for you?

Given the current discourse on educational outcomes and wellbeing for children and young people in light of COVID, a shift away from deficit models is necessary now more than ever. Deficit models see students as the problem and this sentiment can often be attached to students from low SES backgrounds. This might be a starting point for you in reframing how you see such issues.

What does this mean for learners?

Reducing Maths Anxiety and improving Maths Achievement is about far more than just equipping learners with skills. It is also about changing the broader systems and structures that impact their educational environments, and I am hopeful for this change.

References

- Richardson, F. C., & Suinn, R. M. (1972). The Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 19, 551–554.

- Devine, A., Fawcett, K., Szűcs, D., & Dowker, A. (2012). Gender differences in mathematics anxiety and the relation to mathematics performance while controlling for test anxiety. Behavioural and Brain Functions. 8, 1–9.

- Hill, F., Mammarella, I. C., Devine, A., Caviola, S., Passolunghi, M. C., & Szűcs, D. (2016). Maths anxiety in primary and secondary school students: Gender differences, developmental changes and anxiety specificity. Learning and Individual Differences, 48, 45-53.

- Dowker, A., Sarkar, A., & Looi, C. Y. (2016). Mathematics anxiety: what have we learned in 60 years?. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 508.

- Kalaycioglu, D. B. (2015). The Influence of Socioeconomic Status, Self-Efficacy, and Anxiety on Mathematics Achievement in England, Greece, Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Turkey, and the USA. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 15, 1391-1401.

- Sammons, P., K. Sylva, E., Melhuish, I., Siraj, B., Taggart, K., Toth, & Smees. R. (2014). Influences on Students’ GCSE Attainment and Progress at Age 16. London: Department for Education.

- McConney, A,. & Perry, L.B. (2010). Socioeconomic status, self-efficacy, and mathematics achievement in Australia: A secondary analysis. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 9, 77-91.

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents, 5, 307-337.

- Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs and mathematical problem-solving of gifted students. Contemporary educational psychology, 21, 325-344.

- Hoffman, B. (2010). “I think I can, but I’m afraid to try”: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and mathematics anxiety in mathematics problem-solving efficiency. Learning and individual differences, 20, 276-283.

- Johnston-Wilder, S., & Lee, C. (2010). Mathematical resilience. Mathematics Teaching, 218, 38-41.

- Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. (2010). The spirit level: Why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Very interesting findings – particularly the link with school but not individual-level SES. It would be interesting to explore what it is in the school environment that explains this finding but totally agree that even though this is a small-scale study it does support the very important argument that we need to move away from a deficit model in thinking about maths anxiety!

LikeLiked by 1 person