By Anna Wong and Paul Yip

Anna Wong studied Music (BA) and Education (PhD) at Cambridge and is currently a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Hong Kong developing innovative school practices for student wellbeing. Her research interests include the therapeutic uses of musical engagement for mental health promotion and suicide prevention.

Paul Yip is the founding director of the Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention at the University of Hong Kong, and chair professor at the university’s Department of Social Work and Social Administration. He is the principal investigator of OPENUP – a 24 hour online emotional support project and the Quality Thematic Network on developing mental wellness for schools in Hong Kong.

The beginning of the academic year is a time for starting anew. Tragically, for some, it is a time for ending their lives. It is tempting to interpret the timing as a sign that school stress is the sole culprit. However, there is rarely a single cause of suicide. An inquiry into suicides of Hong Kong students in 2013-16 revealed that over 97% had experienced stressors in multiple areas such as family and school.

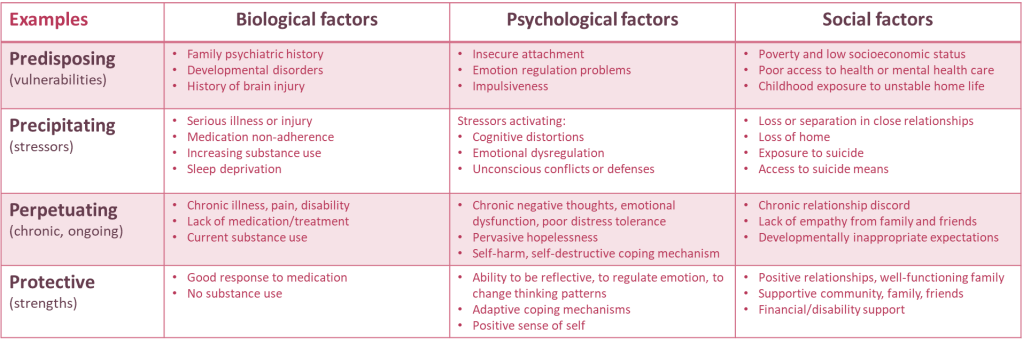

What factors influence individuals’ suicidal ideation?

Often when suicidal behaviour occurs, attention is directed towards the individual’s characteristics and immediate circumstances, yet temporal and environmental factors are also influential. Instability in the larger environment is linked to the individual’s stress and capacity to cope. In Hong Kong, school staff are doing the best they can to ensure students’ learning is not compromised by prolonged class disruption and shortened school days. The pressure to achieve scholastic targets is high, but without considering students’ wellbeing, those already vulnerable will be at high risk of feeling defeated and trapped, unable to cope with their distress – experiences that are strongly associated with the emergence of suicidal thoughts [1]. School, however, can and should be a place for promoting student wellbeing.

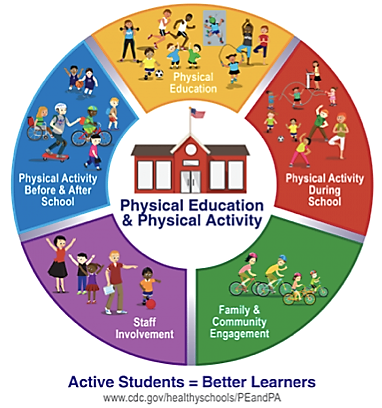

How can physical education in schools promote students’ wellbeing?

Since September this year, a SEN Coordinator has been keeping a close eye on Primary Year 6 students, who are experiencing the peak season of preparation for secondary school entry tests and interviews – a very intense period especially for those struggling academically. On a good day, his students would sit through the most part of the lesson in a calm and engaging manner. On a bad day, students would chat incessantly, act out, scream, and even fight. Disciplinary and counselling measures inevitably followed. However, an extraordinary episode was observed after a very bad day. At first, students entered his classroom all sweaty and looking tired having just finished a 40-minute PE lesson. Within minutes, however, they transformed into bright-eyed and focused individuals. Throughout the lesson, they asked good questions and gave imaginative responses to a discussion on C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. He attributed the transformation to exercise, which he found to be particularly effective in helping students focus.

Exercise and Mental Health

Exercise is crucial for brain health and the regulation of cognitive and affective functions and mood, all of which play an important role in preventing (vs. perpetuating) suicidal thoughts and behaviour. Yet, in the past two years, we have seen a significant reduction in PE lessons. Likewise, our review [2] found that the biological component is often neglected in student wellbeing programs. The SEN Coordinator reminds us that now, more than ever, students need their exercise in school for better mental health. While physical exercise may appear to compete with academic learning over school time, they need to coexist because good mental health is an essential element for effective learning.

What is the influence of music therapy on students’ wellbeing?

Elsewhere, on a music therapy program led by Hong Kong University’s Centre on Suicide Research and Prevention, a “third space” was created in school for at-risk students to find rest, resources, and companionship to explore together their innermost struggles without judgement. Results were promising – students in music therapy experienced a reduction in negative mood and many appreciated the freedom to play and express themselves as wished, instead of following instructions and expectations.

Music for wellbeing

Further, we learned that the most vulnerable students perceived having nowhere to escape and no one to turn to when they experienced difficulties in their family or school lives. When words failed, music became a tool they can use to connect with their feelings and begin to express them in the company of school peers going through similar struggles. Importantly, the experience of music therapy group enhanced students’ social connectedness as well as school belonging, which is defined as “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school social environment” [3]. School belonging is linked to lower absence and drop-out, better wellbeing, learning motivation, and academic achievement.

While music therapy proved to be effective for the few, there is great potential for developing “music for wellbeing” activities to serve the whole school community. These can be taught so that teachers can incorporate them into classes and routines, creating a universal space for young people to find restoration and support instead of unbearable distress and isolation.

There can be no health without mental health. We all need to recognize how common student distress is and make student wellbeing a top priority. Research suggests that leisurely pursuits provide essential nutrients and energy for more effective learning. Why not begin by turning regular school features like exercise and music into valuable resources for student mental health?

References

[1] O’Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational–volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1754), 20170268.

[2] Wong, A., Chan, I., Tsang, C. H. C., Chan, A. Y. F., Shum, A. K. Y., Lai, E. S. Y. & Yip, P.S.F. (2021). A local review on the use of bio-psycho-social model in school-based mental health promotion. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 12:691815.

[3] Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E.. (1993). The Relationship of School Belonging and Friends’ Values to Academic Motivation among Urban Adolescent Students. The Journal of Experimental Education 62, 60–71.

Very interesting Anna. It seems as though there are two strands to your work – the first focussing on mental ill health and the other on wellbeing. What do you think the connection is between these?

LikeLike

I usually think of mental health and wellbeing in terms of the three-level pyramid used in public health, where prevention at the bottom primary level is the foundation of population health. If the majority’s mental health improves by a little using a preventive approach, e.g. regularly engaging in an activity that makes one healthy and happy, the positive impact on population health will be much bigger than trying to improve mental health of individuals (those at the top of the pyramid) who already show symptoms of distress, illness, or crisis.

At the same time, the presence and needs of at-risk individuals are fully acknowledged and that’s why professional and therapeutic approaches should be readily available and accessible especially by vulnerable groups.

LikeLike