David Baker, March 2024

There is a debate to be had about the role of literature in a research study of wellbeing. There are three reasons for this. Firstly, wellbeing is a live issue, with new literature appearing all the time, much of it containing new data. Secondly, it is a multifaceted phenomenon. I would even call it a portmanteau concept, a large and somewhat battered suitcase into which a great many untidy ideas can be squeezed. And lastly, the literature is dauntingly vast, produced not only by academics but by governments, international organisations and interest groups such as Education Support and the National Education Union. They all have axes to grind. Truly a ‘Pandora’s box’ as Ros McLellan recently described it (McLellan et al., 2022, p.3)

So the question arises – when is enough literature enough literature?

I’d like to offer three ways of finding the answer, all of which I have used in my own thesis.

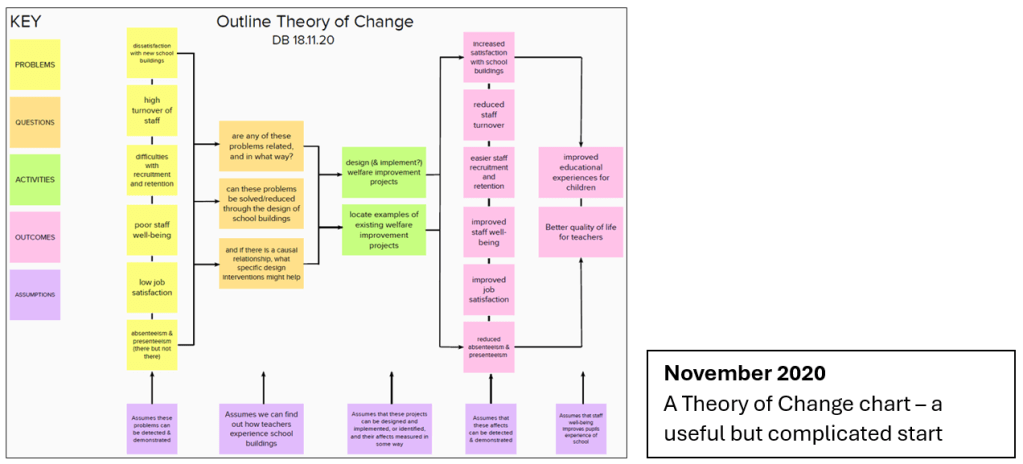

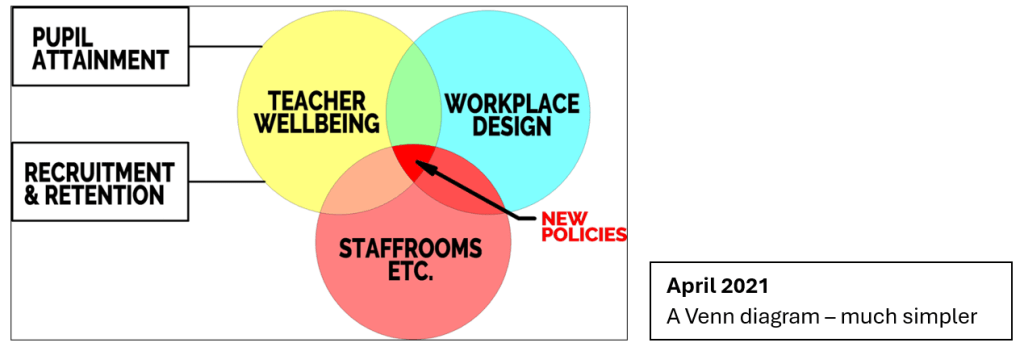

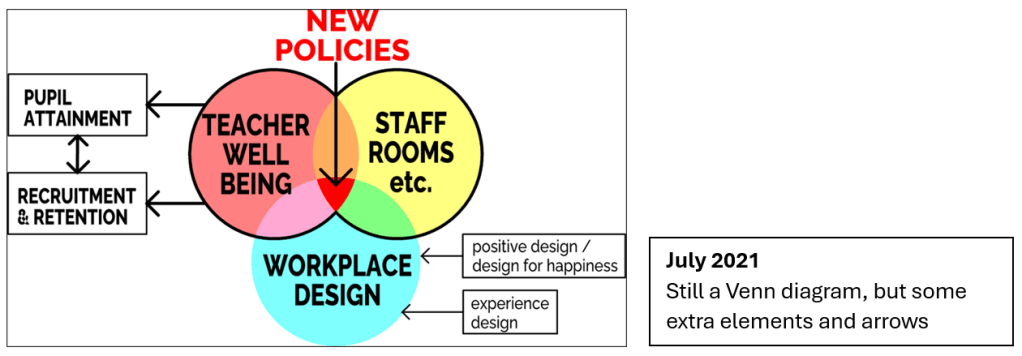

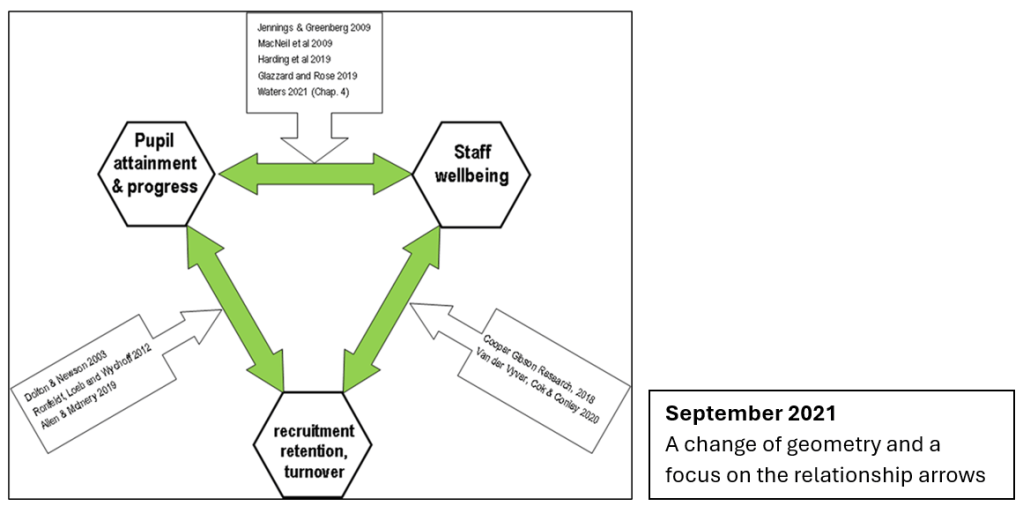

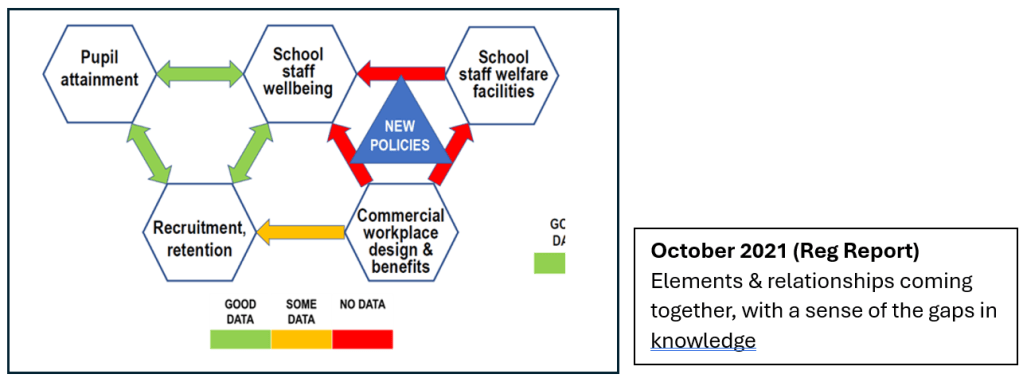

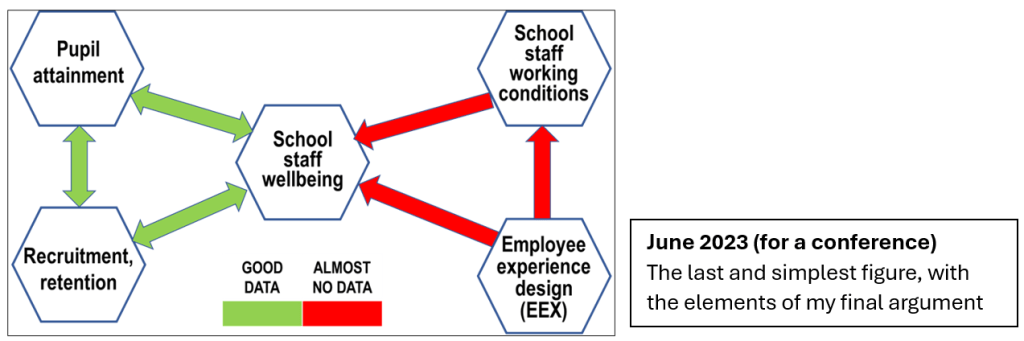

First, it is to start with the figures, to start by drawing diagrams that illustrate the basic elements of your argument. As your ideas change during your project, redraw these figures, time and time again. The very act of putting words into boxes and joining them with arrows helps to define the scope of the literature that you must search for.

Here are some of the diagrams from my research project, arranged chronologically.

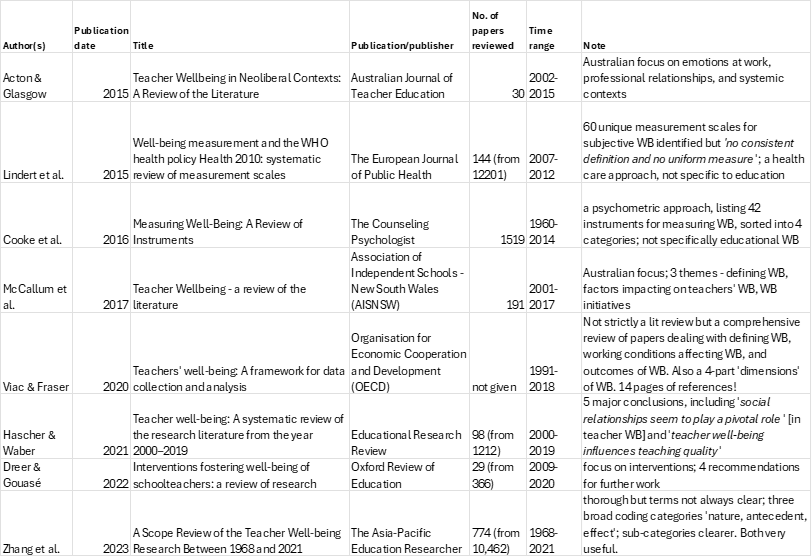

The second technique is to locate elements in your study within systematic literature reviews, as this will clarify the extent of your detailed searching. The reviews provide an overview of papers that meet the reviewers’ criteria, when they conducted their search. The tabulated formats in these reviews can guide you quickly to the kind of material that you are looking for.

For my own project, I required two things. I needed a simple definition of wellbeing that could be used in my case study interviews to answer the inevitable question ‘what do you mean by wellbeing?’. Many of the available academic definitions are cumbersome and try to encompass too many ideas. I needed a definition that fitted the generally accepted understanding of wellbeing in everyday conversation, here and now. Finally, I needed a system for surveying wellbeing at my case study schools that would not be too demanding or take too long to answer – school staff are stressed enough. Helpfully and pragmatically, Qualtrics (the software I used to design my questionnaire) gives guidance on simplifying the survey language and structure to increase the likelihood of receiving responses.

I therefore carried out my initial search by looking for the words ‘review’ and ‘wellbeing’ in the title (‘systematic’ would be a bonus), and I only looked for reviews produced after 2015 as these would represent current thinking. This thus became a small lit review in its own right and I have tabulated the resulting finds in the table below.

I found the definition and survey format that I was looking for in two of the reviews, Lindert et al (2015) and Cooke et al. (2016). Cooke et al. noted that the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) (Tennant et al., 2007) offered ‘a wide conception of wellbeing’ (p.743), had only 14 questions, and should take about 5 minutes to complete. I might have found WEMWBS in other ways, for instance it is the system used by Education Support in their annual wellbeing index. However, the reviews accelerated the process and gave me the reassurance that WEMWBS would perform well against others that are available.

The final way to decide when enough is enough is simply to draw a line in time, to say my literature review stopped at such and such a date. This sounds like a good idea. But when to draw the line? Had I done that in October 2021 (the month when I’d planned to finish my literature review) I would have missed four excellent and important recent reviews (the last four in my table above) and one vital book (McLellan et al, 2022). So now, finally, in Week 5 of my thesis write-up, in January 2024, I have decided. NO MORE literature review! NO MORE downloads!

REFERENCES

Cooke, P. J., Melchert, T. P., & Connor, K. (2016). Measuring Well-Being: A Review of Instruments. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(5), 730–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016633507

Lindert, J., Bain, P. A., Kubzansky, L. D., & Stein, C. (2015). Well-being measurement and the WHO health policy Health 2010: Systematic review of measurement scales. The European Journal of Public Health, 25(4), 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku193

Ros McLellan, Carole Faucher, & Venka Simovska. (2022). Wellbeing and Schooling: Cross Cultural and Cross Disciplinary Perspectives (Issue volume 4). Springer. https://ezp.lib.cam.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=3280472&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., Parkinson, J., Secker, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

This is such a useful blog post for researchers starting out in the field. I really liked the way you’ve shown the evolution of your thinking in visual format, David – although I guess I would expect that from an architect! Have your really stopped downloading literature – I bet not – you’ll still be doing that right up to the day of your viva, even if you aren’t able to include it in your thesis writing 🙂

LikeLike